In the year 1805, when the modern absinthe recipe was put into production by Henri-Louis Pernod in Pontarlier, France, the eventual bans put in place by some nations governing the sale of absinthe were over a century off. In fact, Pernod and the legions of absinthe drinkers in France, Switzerland, and the Czech Republic would not live to see the day of an absinthe ban. However, the same intellectual, artistic culture that gave absinthe its massive popularity would, in the short span of only a century, give absinthe its end as the drink of choice for many Western Europeans.

In the year 1805, when the modern absinthe recipe was put into production by Henri-Louis Pernod in Pontarlier, France, the eventual bans put in place by some nations governing the sale of absinthe were over a century off. In fact, Pernod and the legions of absinthe drinkers in France, Switzerland, and the Czech Republic would not live to see the day of an absinthe ban. However, the same intellectual, artistic culture that gave absinthe its massive popularity would, in the short span of only a century, give absinthe its end as the drink of choice for many Western Europeans.

Artistic Impact

Edgar Degas, a Parisian painter and social conservative, struck the  first major blow against absinthe with his 1876 painting, L’Absinthe, which depicted the alleged stupor and lethargy that would slowly become the accepted traits of absinthe drinkers, or “addicts,” as they were called. The subjects of the painting were famed Parisian socialites of the time, actress Ellen Andrée and painter Marcellin Desbouti. L’Absinthe was coolly received in early Paris exhibitions and placed in storage, where it stayed until 1892, by which time unease about the prevalence of absinthe had really taken hold. In its first showing after being taken out of storage, legend has it that the painting was literally booed off its easel. A later exhibition one year later in England lit a fire under the absinthe controversy, but curiously, absinthe was never banned in the United Kingdom.

first major blow against absinthe with his 1876 painting, L’Absinthe, which depicted the alleged stupor and lethargy that would slowly become the accepted traits of absinthe drinkers, or “addicts,” as they were called. The subjects of the painting were famed Parisian socialites of the time, actress Ellen Andrée and painter Marcellin Desbouti. L’Absinthe was coolly received in early Paris exhibitions and placed in storage, where it stayed until 1892, by which time unease about the prevalence of absinthe had really taken hold. In its first showing after being taken out of storage, legend has it that the painting was literally booed off its easel. A later exhibition one year later in England lit a fire under the absinthe controversy, but curiously, absinthe was never banned in the United Kingdom.

While artists and intellectuals became known for – and often identified by – their use of absinthe, they also had a hand in shaping public opinion of the drink. In addition to Degas’ iconic L’Absinthe, other  famed painters and writers portrayed absinthe in a negative light.

famed painters and writers portrayed absinthe in a negative light.

Viktor Oliva, a Czech painter and illustrator, fell in love with absinthe after he moved to the thriving art district of Montmartre, in Paris. Oliva’s most famous work, “Absinthe Drinker,” is a depiction of a lone man sitting in a café, his hat lays on the table next to him. The subject’s head is propped up by his hand, and he’s staring dully at a green apparition, la fee verte, the green lady, sitting lustily on the table before him.

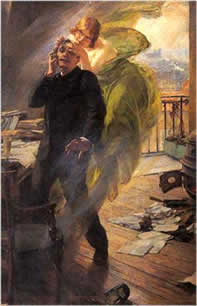

Albert Maignan’s “Green Muse” is a similar work to Oliva’s “Absinthe Drinker.” In “Green Muse,” a poet surrenders to “the green fairy,” (another name given to absinthe) as he stumbles around his grimy flat.

The mind-altering effects of absinthe, proved through art and reputation, would soon become cause for backlash.

Temperance and the Wine Shortage

One of the causes for absinthe’s popularity was the Great French Wine Blight. The catalyst for the loss of thousands of French vineyards in the mid-1800’s was the phylloxera, a parasitic aphid carried over at some point in the same century from its native North America. The aphid fed on grapes and ravaged French vineyards for as long as a decade. Wine production in France hit a standstill. French soldiers who had been using absinthe as a cure for everything from malaria to migraines found the drink to be a worthy replacement for the lacking wine.

As the vineyards recovered and the French winemakers sought to begin doing business again, the French affection for absinthe proved a worthy adversary. Though France had long been known as a winemaking and wine consuming society, from the time of the 1840’s through the 1880’s, absinthe was – much like wine had been and is today – the drink of choice for French people of all classes. The French winemakers, in an effort to win their customers away from absinthe, joined forces with the temperance movement to discredit the enjoyment of absinthe. “The Green Lady” became the “Green Curse.” The psychoactive pleasuresof absinthe were now classified as toxic side-effects and, worse, the result of madness. Only a century previous, Dr. Pierre Ordinaire’s Swiss recipe was used as a solution for many of the negative effects absinthe was rumored to cause.

The self-interest of French winemakers went hand in hand with the burgeoning temperance movement. France’s time of peace, prosperity, and progress, the Belle Epoque, took hold after the Franco-Prussian War. It was a time of borderline spiritual enlightenment as well as empowerment for women. The lethargy and “loose ways” of café culture was portrayed as a poor way to live. Absinthe, once a beloved substance, was now portrayed as a scourge. The momentum behind the temperance movement built throughout the late 1800’s, and in 1905, it received its rallying cry in the name of Jean Lanfray.

Jean Lanfray and the Absinthe Scandal

In this day and age, the story of Jean Lanfray is, unfortunately, none too shocking. However, at the turn of the century, the crime of Jean Lanfray was an unspeakable horror. The prevailing attitude in France at the turn of the 20th century was decidedly anti-absinthe. When Jean Lanfray, a French laborer, spent a fateful day in 1905 drinking himself to madness, a madness which led to the murder of his pregnant wife and two children, investigators found that Lanfray had taken only two drinks of absinthe. Despite the facts, the temperance and winemaking interests turned Lanfray’s crime into a scandal of the lowest order, and placed the full brunt of the blame on the “Green Curse.” The charges stuck, and absinthe lost out in the court of public opinion. It would be another ten years before France officially outlawed absinthe, but after the Lanfray scandal, the reputation of absinthe had sunk to irreparable depths.

The following year, France’s neighboring nation, Belgium, outlawed absinthe. Though the first case of absinthe being officially outlawed by a national government came as early as 1898, the early 1900’s saw a wave of absinthe bans throughout the world in response to the tainted claims made against La Fee verte. Absinthe went underground, and was enjoyed by connoisseurs in many parts of the world through its decades-long ban, whether legal or illegal. The absinthe bans had the reverse effect, over time, of digging the reputation of the drink back out of the gutter – legends and speculation grew over time about the hallucinatory, calming effects of thujone, the psychoactive chemical in absinthe. The modern revival of absinthe is a direct result from its “mythic” status, not as the drink that could drive men mad, but as a lost wonder beverage enjoyed by many prior to its untimely and unfair prohibition.